Category: Definitions

nondelegation doctrine

“… the Supreme Court has limited the types of authority and functions that Congress can delegate to a purely private entity.”

The non-delegation doctrine is the principle that Congress cannot delegate its legislative powers or lawmaking ability to other entities. This prohibition typically involves Congress delegating its powers to administrative agencies or to private organizations. Thus, the non-delegation doctrine is most commonly used in connection with administrative law and constitutional law.

ArtI.S1.5.1 Overview of Nondelegation Doctrine

Article I, Section 1:

All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

The nondelegation doctrine is rooted in certain separation of powers principles.1 In limiting Congress’s power to delegate, the nondelegation doctrine exists primarily to prevent Congress from ceding its legislative power to other entities not vested with legislative authority under the Constitution. As interpreted by the Court, the doctrine seeks to ensure that legislative decisions are made through a bicameral legislative process by the elected Members of Congress or governmental officials subject to constitutional accountability.2 Reserving the legislative power for a bicameral Congress was “intended to erect enduring checks on each Branch and to protect the people from the improvident exercise of power by mandating certain prescribed steps.” 3

The nondelegation doctrine, however, does not require complete separation of the three branches of government, and its continuing strength is the question of much debate.4 In its nondelegation jurisprudence, the Supreme Court has recognized the need and importance of coordination among the three branches of government so long as one branch does not encroach on the “constitutional field” of another branch.5 The nondelegation doctrine seeks to distinguish the constitutional delegations of power to other branches of government that may be “necessary” for governmental coordination from unconstitutional grants of legislative power that may violate separation of powers principles.6Footnotes1See Loving v. United States, 517 U.S. 748, 758 (1996) ( “Another strand of our separation-of-powers jurisprudence, the delegation doctrine, has developed to prevent Congress from forsaking its duties.” ). For discussion of the separation of powers, see Intro.7.2 Separation of Powers Under the Constitution.

2See Immigration & Naturalization Serv. v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919, 959 (1983) ( “There is no support in the Constitution or decisions of this Court for the proposition that the cumbersomeness and delays often encountered in complying with explicit constitutional standards may be avoided, either by the Congress or by the President. With all the obvious flaws of delay, untidiness, and potential for abuse, we have not yet found a better way to preserve freedom than by making the exercise of power subject to the carefully crafted restraints spelled out in the Constitution.” ) (citations omitted). See also Dep’t of Transp. v. Ass’n of Am. R.R., 575 U.S. 43, 61 (2015) (Alito, J., concurring) ( “The principle that Congress cannot delegate away its vested powers exists to protect liberty. Our Constitution, by careful design, prescribes a process for making law, and within that process there are many accountability checkpoints. It would dash the whole scheme if Congress could give its power away to an entity that is not constrained by those checkpoints. The Constitution’s deliberative process was viewed by the Framers as a valuable feature, not something to be lamented and evaded.” ) (citations omitted); Indus. Union Dep’t, AFL-CIO v. API, 448 U.S. 607, 687 (1980) ( “It is the hard choices, and not the filling in of the blanks, which must be made by the elected representatives of the people. When fundamental policy decisions underlying important legislation about to be enacted are to be made, the buck stops with Congress and the President insofar as he exercises his constitutional role in the legislative process.” ).

3Immigration & Naturalization Serv. v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919, 957–58 (1983).

4Marshall Field & Co. v. Clark, 143 U.S. 649, 692 (1892); Wayman v. Southard, 23 U.S. (10 Wheat.) 1, 42 (1825).

5J.W. Hampton, Jr. & Co. v. United States, 276 U.S. 394, 406 (1928).

6Id. at 406. See also Chadha, 462 U.S. at 944 ( “[T]he fact that a given law or procedure is efficient, convenient, and useful in facilitating functions of government, standing alone, will not save it if it is contrary to the Constitution. Convenience and efficiency are not the primary objectives—or the hallmarks—of democratic government.” ).

In J.W. Hampton v. United States, 276 U.S. 394 (1928), the Supreme Court clarified that when Congress does give an agency the ability to regulate, Congress must give the agencies an “intelligible principle” on which to base their regulations. This standard is viewed as quite lenient, and has rarely, if ever, been used to strike down legislation.

In A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495 (1935), the Supreme Court held that “Congress is not permitted to abdicate or to transfer to others the essential legislative functions with which it is thus vested.”

ArtI.S1.6.5 Private Entities and Legislative Power Delegations

Article I, Section 1:

All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

In contrast to the relative latitude given to delegations to other branches of the government under the “intelligible principle” standard,1 the Supreme Court has limited the types of authority and functions that Congress can delegate to a purely private entity.2 The seminal case addressing delegations to a private entity is Carter v. Carter Coal Co.3 In Carter Coal, the Supreme Court invalidated the Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1935, a law that granted a majority of coal producers and miners in a given region the authority to impose maximum hour and minimum wage standards on all other miners and producers in that region.4 The Court reasoned that by conferring on a majority of private individuals the authority to regulate “the affairs of an unwilling minority,” the law was “legislative delegation in its most obnoxious form; for it is not even delegation to an official or an official body, presumptively disinterested, but to private persons whose interests may be and often are adverse to the interests of others in the same business.” 5 The Court did not apply the “intelligible principle” standard, but instead focused on the regulatory and “coercive” power given to private entities over its competitors and the due process concerns raised by such delegations.6

Although Carter Coal concerned the delegation of authority to private entities and not governmental bodies, some courts and commentators have suggested that the Carter Coal decision may more accurately be viewed as a due process case.7 The Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause prohibits the Federal Government8 from depriving any person of “life, liberty, or property without due process of law,” 9 which the Court has interpreted as establishing certain principles of fundamental fairness, including the notion that decision makers must be disinterested and unbiased.10 In striking down the delegation to coal producers and miners to impose standards on other producers and miners, the Supreme Court in Carter Coal centered its analysis on the coercive power that the majority could exercise over the “unwilling minority.” 11 The opinion articulated the due process problems involved with providing regulatory authority to private entities, stating:

The difference between producing coal and regulating its production is, of course, fundamental. The former is a private activity; the latter is necessarily a governmental function, since, in the very nature of things, one person may not be entrusted with the power to regulate the business of another, and especially of a competitor. And a statute which attempts to confer such power undertakes an intolerable and unconstitutional interference with personal liberty and private property. The delegation is so clearly arbitrary, and so clearly a denial of rights safeguarded by the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment, that it is unnecessary to do more than refer to decisions of this court which foreclose the question.12

The Court’s reasoning in Carter Coal suggests that delegating authority to coal producers and miners to impose standards on its competitors is in tension with both the nondelegation doctrine and the Due Process Clause.13

After its Carter Coal decision, the Supreme Court did not comprehensively ban private involvement in regulation. In the context of private parties aiding in regulatory functions and decisions, the Court has indicated that Congress may empower a private party to play a more limited and supervised role in the regulatory process. For example, in Currin v. Wallace,14 the Court upheld a law that authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to issue a regulation respecting the tobacco market, but only if two-thirds of the growers in that market voted for the Secretary to do so.15 In distinguishing Carter Coal, the Court stated that “this is not a case where a group of producers may make the law and force it upon a minority.” 16 Rather, it was Congress that had exercised its “legislative authority in making the regulation and in prescribing the conditions of its application.” 17

Similarly, in Sunshine Anthracite Coal Co. v. Adkins,18 the Supreme Court upheld a provision of the Bituminous Coal Act of 1937,19 which authorized private coal producers to propose standards for the regulation of coal prices.20 Those proposals were provided to a governmental entity, which was then authorized to approve, disapprove, or modify the proposal.21 The Court approved this framework, heavily relying on the fact that the private coal producers did not have the authority to set coal prices, but rather acted “subordinately” to the governmental entity (the National Bituminous Coal Commission).22 In particular, the Sunshine Anthracite Court noted that the Commission and not the private industry entity determined the final industry prices to conclude that the “statutory scheme” was “unquestionably valid.” 23

In the same vein as Carter Coal, the Supreme Court in Currin and Sunshine Anthracite did not evaluate whether Congress laid out an “intelligible principle” guiding the delegations to the private entities. Rather than applying the “intelligible principle” standard, the Court reviewed whether the responsibilities given to the private entities were acts of legislative or regulatory authority.24 In these nondelegation cases involving private entities, the Court drew the “line which separates legislative power to make laws, from administrative authority” to administer laws.25 In both Currin and Adkins, the Court reasoned that the private entities did not exercise legislative power because they did not impose or enforce binding legal requirements.26 Because the private entity’s responsibilities were primarily administrative or advisory, the Court determined that the statutes did not violate the nondelegation doctrine.27Footnotes1See ArtI.S1.5.3 Origin of Intelligible Principle Standard.

2See A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495, 537 (1935) (holding that delegation to trade and industrial associations of the power to develop codes of “fair competition” for the poultry industry “is unknown to our law and utterly inconsistent with the constitutional prerogatives and duties of Congress” ).

4Id. at 311–12.

5Id. at 311. The Court appeared to characterize the wage and hour provisions as an unlawful “delegation” to a private entity, but also held that the provision in question was “clearly a denial of rights safeguarded by the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment,” id. at 311–12, leading some to question whether Carter should be considered a nondelegation case at all.

6Seeid. at 311 ( “The difference between producing coal and regulating its production is, of course, fundamental. The former is a private activity; the latter is necessarily a governmental function, since, in the very nature of things, one person may not be entrusted with the power to regulate the business of another, and especially of a competitor.” ).

7At least one court has debated on whether Carter Coal is a nondelegation or due process decision. See Ass’n of Am. R.R. v. Dep’t of Transp., 821 F.3d 19, 31 (D.C. Cir. 2016) (explaining that it was unclear what aspect of the “delegation [in Carter Coal] offended the Court. By one reading, it was the Act’s delegation to ‘private persons rather than official bodies. By another, it was the delegation to persons ‘whose interests may be and often are adverse to the interests of others in the same business’ rather than persons who are ‘presumptively disinterested,’ as official bodies tend to be. Of course, the Court also may have been offended on both fronts. But as the opinion continues, it becomes clear that what primarily drives the Court to strike down this provision is the self-interested character of the delegatees’ . . . .” ).

8The Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, by its very nature, only applies to the actions of the Federal Government. See Farrington v. Tokushige, 273 U.S. 284, 299 (1927) ( “[T]he inhibition of the Fifth Amendment—’No person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law’—applies to the federal government and agencies set up by Congress for the government of the Territory.” ). For discussion of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, see Amdt5.5.1 Overview of Due Process. The Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause as applied to actions of the states is discussed at Fourteenth Amendment, Section 1.

9U.S. Const. amend. V. See also Marshall v. Jerrico, Inc., 446 U.S. 238, 242 (1980) ( “The Due Process Clause entitles a person to an impartial and disinterested tribunal in both civil and criminal cases.” ); Carter Coal, 298 U.S. at 311; Eubank v. City of Richmond, 226 U.S. 137, 143–44 (1912) (invalidating a city ordinance on the grounds that it established “no standard by which the power thus given is to be exercised; in other words, the property holders who desire and have the authority to establish the line may do so solely for their own interest, or even capriciously. . . . ” ). See Amdt5.5.1 Overview of Due Process.

10See, e.g., Marshall, 446 U.S. at 242.

11Carter Coal, 298 U.S. at 311.

12Id. at 311–12.

13The intersection of the Due Process Clause and the nondelegation doctrine as illustrated by the Court’s decision in Carter Coal may arise when Congress delegates authority to government-created corporations that have both public and private aspects. For example, in Department of Transportation v. Association of American Railroads, the Supreme Court held that “Amtrak is a governmental entity, not a private one” for purposes of reviewing Congress’s power to delegate regulatory authority to Amtrak, a for-profit entity created by Congress. Dep’t of Transp. v. Ass’n of Am. R.R., 575 U.S. 43, 45, 54 (2015). The Court, however, did not reach the issue of whether the delegation of coercive power given to Amtrak over its competitors violates the Due Process Clause or the nondelegation doctrine. Id. at 55–56.

15Id. at 6.

16Id. at 15.

17Id. at 16.

19Pub. L. No. 75–48, 50 Stat. 72 (1937).

20Sunshine Anthracite Coal Co. v. Adkins, 310 U.S. at 388–89.

21Id. at 388.

22Id. at 399.

23Id.

24Id. at 388–89; Currin v. Wallace, 306 U.S. 1, 15–16 (1939).

25United States v. Grimaud, 220 U.S. 506, 517 (1911).

26Sunshine Anthracite Coal Co. v. Adkins, 310 U.S. 381, 388–89 (1940); Currin, 306 U.S. at 15–16.

27Id.

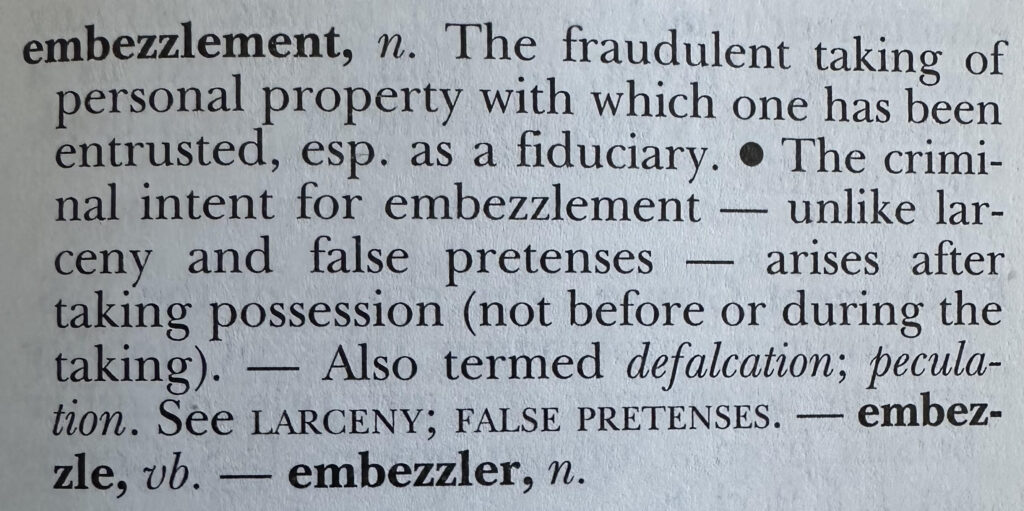

embezzlement: Black’s Law Dictionary Definition:

“embezzlement, n. The fraudulent taking of personal property with which one has been entrusted, esp. as a fiduciary. • The criminal intent for embezzlement — unlike larceny and false pretenses – arises after taking possession (not before or during the taking). — Also termed defalcation; peculation. See LARCENY; FALSE PRETENSES. — embez-zle, ub. — embezzler, n.”

“embezzlement, n. The fraudulent taking of personal property with which one has been entrusted, esp. as a fiduciary. • The criminal intent for embezzlement — unlike larceny and false pretenses – arises after taking possession (not before or during the taking). — Also termed defalcation; peculation. See LARCENY; FALSE PRETENSES. — embez-zle, ub. — embezzler, n.”

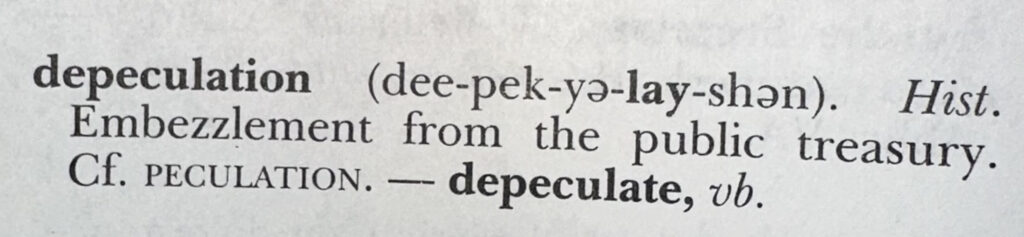

depeculation: Black’s Law Dictionary Definition:

depeculation:

“Embezzlement from the public treasury.”

depeculation

“depeculation (dee-pek-ya-lay-shan). Hist.

Embezzlement from the public treasury.

Cf. PECULATION. — depeculate, ub.”

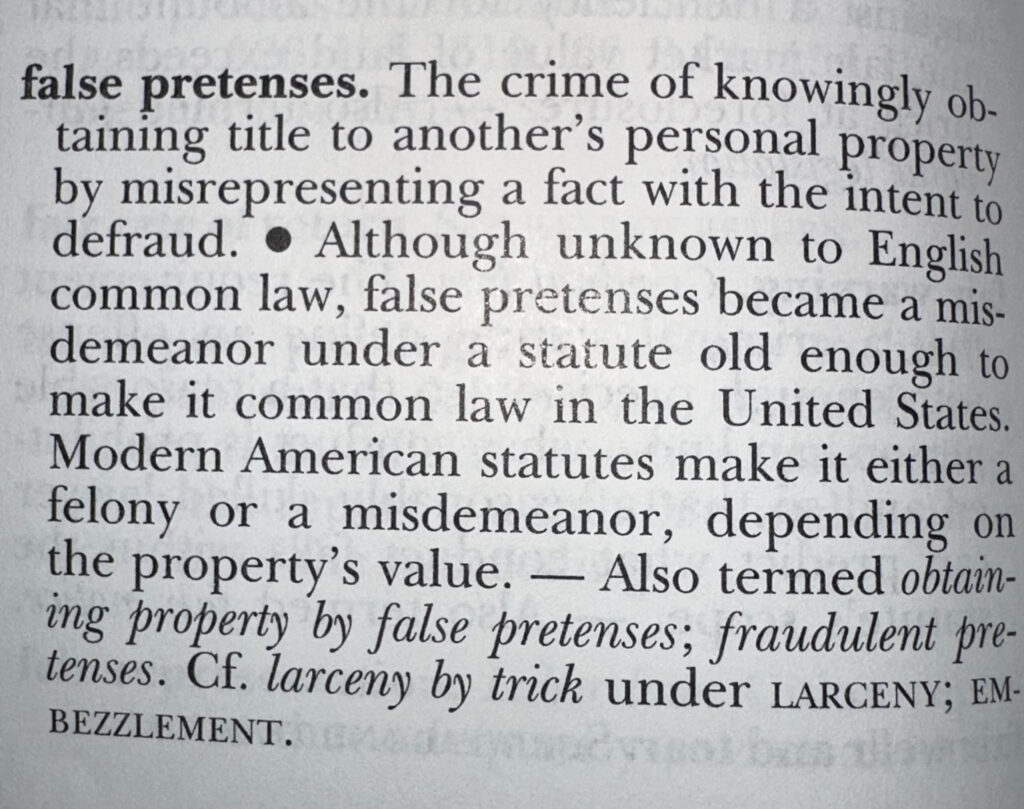

FALSE PRETENSES: Black’s Law Dictionary Definition:

“false pretenses: The crime of knowingly obtaining title to another’s personal property by misrepresenting a fact with the intent to defraud. “

FALSE PRETENSES

“false pretenses. The crime of knowingly obtaining title to another’s personal property by misrepresenting a fact with the intent to defraud. • Although unknown to English common law, false pretenses became a misdemeanor under a statute old enough to make it common law in the United States.

Modern American statutes make it either a felony or a misdemeanor, depending on the property’s value. — Also termed obtaining property by false pretenses; fraudulent pretenses. Cf. larceny by trick under LARCENY; EMBEZZLEMENT.”

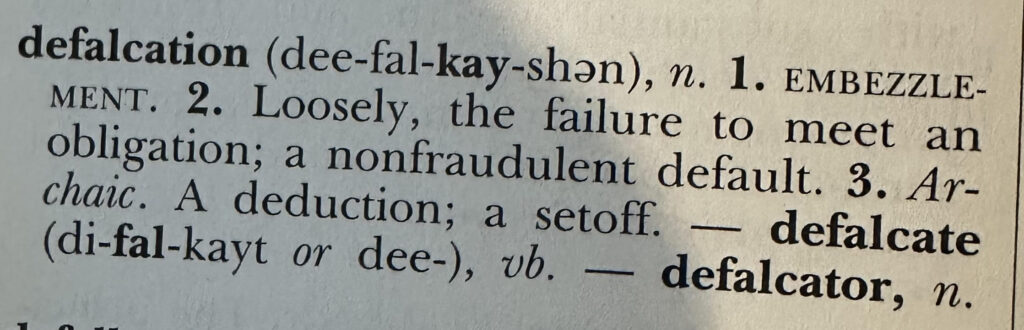

defalcation: Black’s Law Dictionary Definition:

“defalcation (dee-fal-kay-shan), n. 1. EMBEZZLE-MENT. 2. Loosely, the failure to meet an obligation; a nonfraudulent default. 3. Ar-chaic. A deduction; a setoff. …”

defalcation

“defalcation (dee-fal-kay-shan), n. 1. EMBEZZLE-MENT. 2. Loosely, the failure to meet an obligation; a nonfraudulent default. 3. Ar-chaic. A deduction; a setoff. – defalcate (di-fal-kayt or dee-), vb. – defalcator, n.”